How fair is it to deliver your exams only in English?

In the 21st century, “accessibility” often includes language, but translating a test into the strongest language of all test takers may not be realistic. Nevertheless, passing or failing a test should not depend on reading proficiency. Tests and exams are a gate for life chances and—unless being proficient in the language of the test is part of the construct being measured—validity can be threatened. For example, a skilled programmer may not pass a programming test due to the high threshold of English proficiency required in order to complete it. An approach that addresses the issue of non-native speakers is essential for tests to be fair. Two assessment experts, John Kleeman, EVP at Learnosity and Questionmark, and our own Steve Dept, co-founder of cApStAn Linguistic Quality Control, recently delivered a webinar where they explored practices to make exams fair and equitable for non-English speakers.

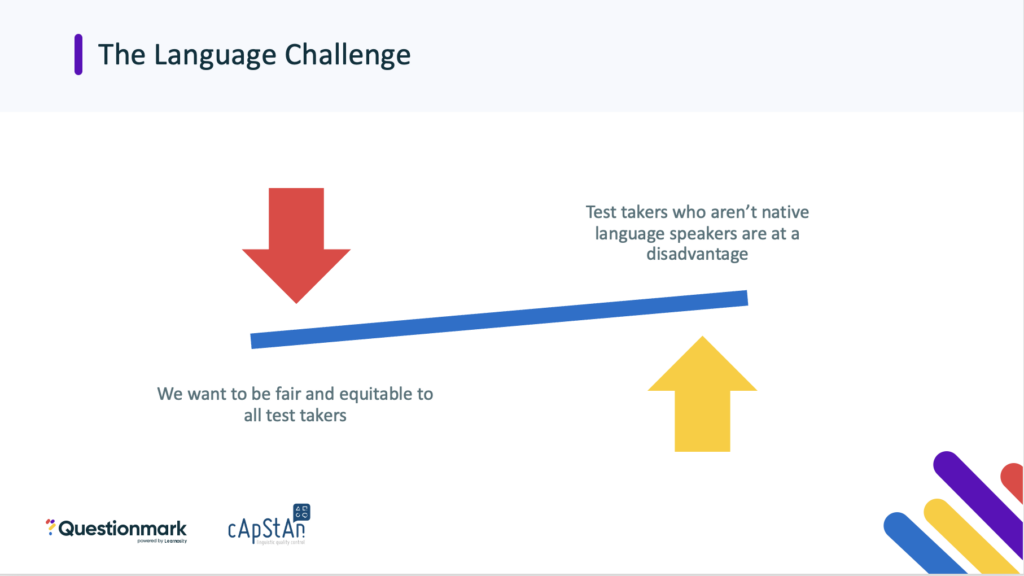

The language challenge

Recent numbers from the US census provide important insights into the language challenge: 22% or 67.8 million US residents speak a language other than English at home. Of these 67.8 million people 62% speak English very well, 19% well, 13% not well and 6% not at all. In other words, even in the US delivering a fair test may be a challenge. In the UK about 92.3% of the population report English as their main language, but then, for many of these, English is their second language. Many test sponsors are also delivering their tests internationally.

Making exams fair and equitable for non-English speakers

Full translation (entire test in L2)

This is a classic when, for example, you have a large population speaking the target language and when there is a good business case for translating the test. But if you translate the entire test, including instructions and prompts, into a second language or more, you can’t just give it to a translation agency and assume that a well translated test will measure the same construct as the original test. For high stakes tests a sophisticated translation design (and a pre-test) are essential in order to achieve comparability of results.

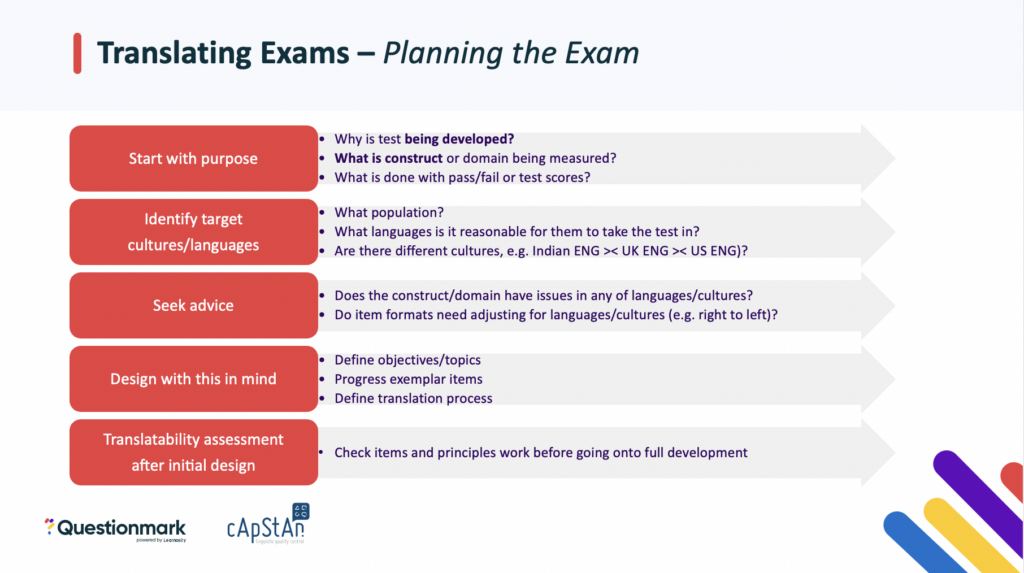

These are some of the key points to consider in designing a test translation and adaptation workflow:

- Translation/adaptation should be embedded in test design

- It is essential to involve specialists at the earliest stages of a translation project

- The time spent optimising the source version and preparing the translation/adaptation process drives quality of translated tests

- Export out of your assessment system to allow translators to work with state-of-the-art technology, and import back seamlessly

- Organize independent quality checks of the translations

- Well-documented compliance with Standards and Guidelines (NACC, ITC/ATP…) remains a cornerstone of test adaptation.

Full translation with possibility to “toggle”

A second possibility, in the case of a full test translation, is to allow the respondents to toggle between the two versions, English and their strongest language, rather than taking the test in their native language. The length of the test and the time on task increases, however. A strong quality assurance design is essential in this approach, too.

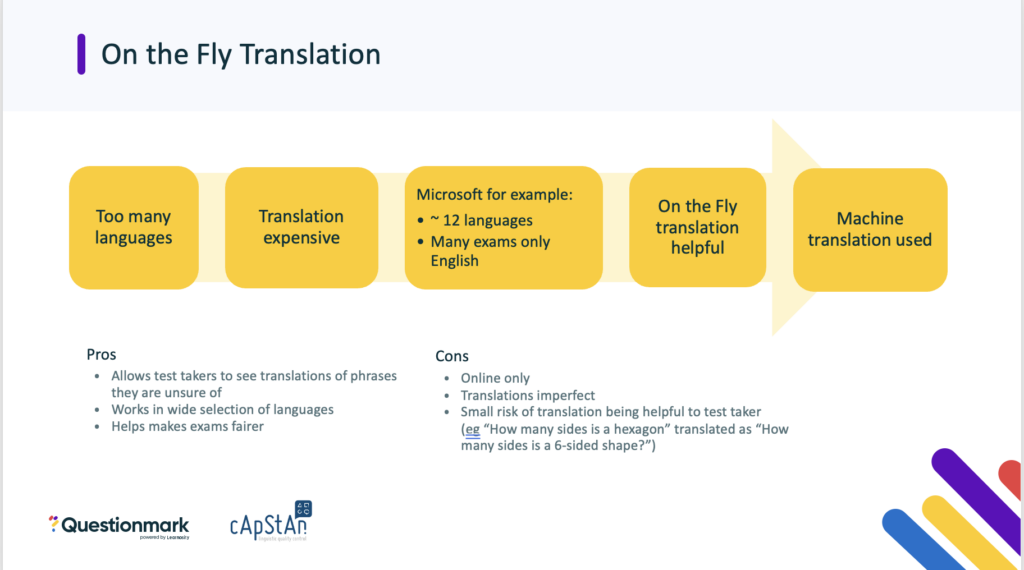

“On the fly” translation

“On the fly” translation only works if your test is delivered on a computer or tablet. When we say “on the fly” we do not mean having an interpreter reading out the test in the different languages; this is about using machine translation. As the original exam is provided in English and the translation is only provided as a support aid, it’s important that the candidate understands and agrees that the machine translation may not be accurate. It is important to include a legal disclaimer about non-accuracy of language at the start of an exam.

Lowering the reading proficiency threshold

This is an efficient way to disentangle language proficiency from skills proficiency. If we want to measure nursing skills, for example, we can make tests more accessible, more intelligible, without however reducing the level of difficulty that is directly related to the skills and knowledge necessary for that profession. A threshold can be defined (e.g., B1 of the CEFR); difficult words/phrases replaced with easier synonyms or paraphrases and long sentences broken up into shorter ones to improve readability. It can also be useful to add an explanation for any difficult “domain-agnostic” terms that cannot easily be replaced by easier synonyms.

Accommodations for L2 speakers

There are also, finally, a number of accommodations that can be made for L2 speakers. These include allowing extra time, giving access to a glossary/dictionary, having an interpreter in the room, or weighting scores depending on the type of questions (e.g. reading proficiency).

How improving support for non-English speakers also benefits test sponsors

In addition to improving fairness there are also benefits to test sponsors in improving support for non-English speakers. These include:

- More test takers [may mean more revenue]

- More test taker diversity

- More credible to stakeholders

- More valid assessments

- More legally defensible

- Broaden access to qualifications, recruitment, etc.

Key take home messages

An approach that deals with non-native speakers is essential for tests to be fair. There is no perfect solution to the problem, but several good approaches are possible including full translation, on-the-fly translation, reviewing reading proficiency and allowing accommodations for non-native speakers. Taking this into account makes exams fairer, may result in a wider reach and bring other benefits.