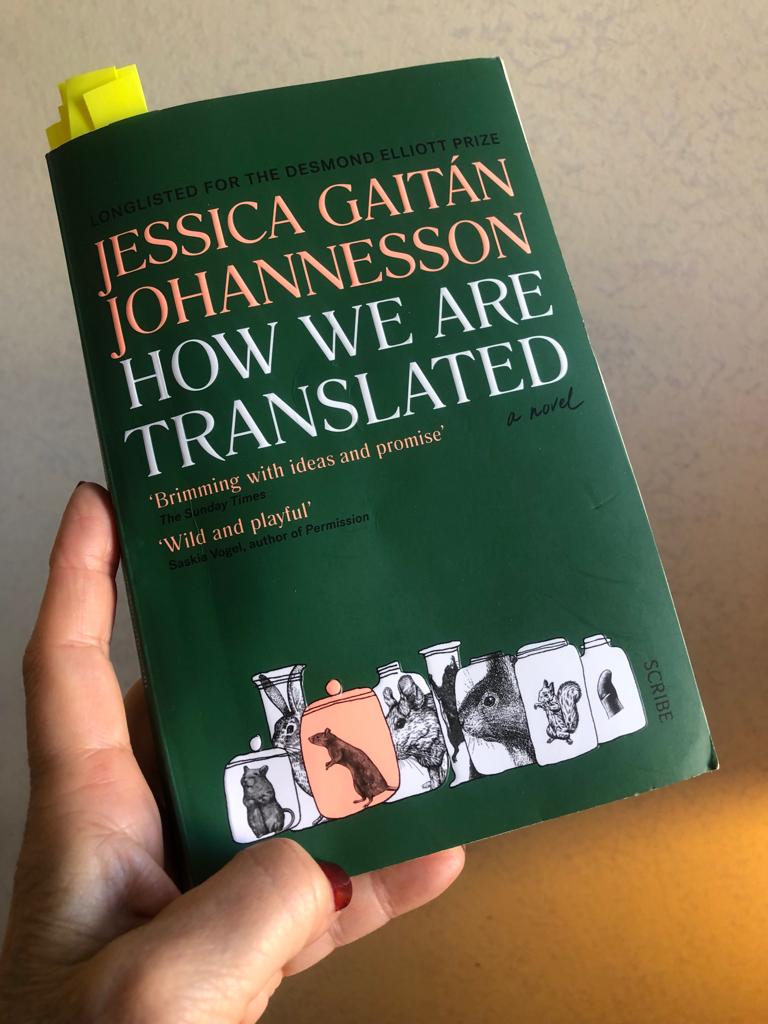

“How we are translated”, a novel which explores the “in-between-ness” of living in several languages at the same time

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

The story

The protagonist, Kristin, is a 24-year old Swedish immigrant in Scotland. She lives with her Brazilian-born Scottish boyfriend Ciaran, whose first language is Portuguese, as he was adopted when he was three years old. They speak English during the first years of their relationship but, when Kristin becomes pregnant, Ciaran decides to to prepare for their future by going on a språkbad (language bath) to learn Swedish. A large part of the novel is dedicated to Ciaran’s often amusing efforts to learn the language through books, Ingmar Bergman films and other information materials, and tackle accents, idiomatic expressions and slang. But, no matter hard he tries this proves complicated and does not really help to bring them closer. Language, culture and identity play a key role also in Kristin’s job: she works for the Edinburgh Immigration Museum, where there is a living history exhibit for each of the different peoples who emigrated to Scotland over the centuries and contributed to its “rich cultural multiplicity.” Kristin fills the role of Solveig, a tenth-century Norse woman, who plays out different rituals and traditions from that period together with her Norse (actor) husband. She is not allowed to speak any English in order to preserve the authenticity of the experience for tourists. Despite the Museum’s claim to “cultural multiplicity” Kristin notes that many immigrant populations are not represented.

The sense of belonging

The unique structure of the book, with its word games and many Swedish-English translations which are laid out graphically into columns, side by side, comes from her own in-between-ness, says Gaitan Johannesson: “What would it look like to sort of inhabit my Swedish-speaking brain and my English-speaking brain at the same time?” “I think it’s fairly impossible to do it completely”, she adds, “but the columns and the literal translations and the hybrid view on language came from wanting to explore what it really means to live in several languages at the same time”. Referencing her own personal experience Gaitán Johannesson says that “moving between countries, being multilingual from the very beginning, and coming from an international family means you’re never fully at home. You’re never fully a stranger, but you’re also never fully at home”. Yes. Belonging is so much more than “just” about language.

Going “exophonic”

“Exophony” is the practice of writing in a language that is not one’s own. In a recent interview Gaitán Johannesson says that when she first started writing in English, about ten years ago, she suffered from “imposter syndrome” and asked herself: “Am I allowed to write in English?” “What would that look like?”…. But then, who does a language really “belong” to? “We all own English, immigrants make English, and people who speak it as a second or third language also own it”, she states. We have written about this topic for our blog (check our articles on this topic at the links below). In recent decades, particularly on account of the increase of migrations, exile, and diaspora “first” and “second” languages, “own” and “foreign”, interact, swap and mix. Encounters with new, foreign cultures and languages often inspire people to write not only in the language of their country of origin, but also in that of the new environment. “Immigration literature is the literature of the future”, according to Italian editor Silvia De Marchi. “It is the literature of those who are moving, who aren’t limited by their own country”. “Non-native speakers bring fresh perspectives to the language”.

Why English?

Gaitán Johannesson says she felt a sense of loss and of “giving up her responsibility” by leaving a “smaller language” behind to write in English. Why English? Was it really a choice? “We want to think that we all make choices”, she says, but actually “we live in a colonial world in which English has a very unique position to create insiders and outsiders and hierarchies”. “When a book appears in English”, she adds, “it is made universal, it becomes a global publication.” Indeed… In an article for our blog provocatively titled “Would Olga Tokarczuk have won the Nobel prize if she had not been translated into English?” we argued that Tokarczuk, who had been a bestselling author in Poland for three decades, only made her international breakthrough thanks to the English translation of the novel “Flights”. As Tokarczk commented at the time of her Nobel Prize “this might not be a desirable state of affairs but for writers from many parts of the world it is a fact of life.” In Gaitán Johannesson’s case writing in English has meant being published in the UK, US and Australia, thus gaining a wider audience, as well as opening the doors to an important literary prize in her country of adoption, and possibly to other interesting opportunities for the future.

Swedish language “purity”

At one point in the novel Ciaran comes across a brochure by the “Stockholm Syndrome, a society for language preservation” (which is completely fictional, we checked), whose name is a word play on the better known syndrome experienced by hostages (see footnote §). According to the Society the Swedish language is in danger and under threat from the hegemony of the English language in Swedish society. “The preservation of the Swedish language is synonymous with the preservation of Swedish national identity. The preservation demands a conscious struggle for Swedish, against English, in the media and science”. Kristin later on in the book reads an article about how most Swedish universities ask post graduate students to write their dissertations in English and that Swedish as a language of science is almost dead. She thinks that it is not so much the Swedish language that is endangered but it its ego, and that Swedish identity is alive and well. We are not aware of any official initiatives in Sweden to protect the language from English (there is a Language Council but we could not find any information on this specific issue) but this is a hot topic in a number of other countries (see our article at this link).

Footnotes

§ The “Stockholm syndrome” is a psychological response wherein a captive begins to identify closely with his or her captors, as well as with their agenda and demands. The name of the syndrome is derived from a bank robbery in Stockholm, Sweden. In August 1973 four employees of Sveriges Kreditbank were held hostage in the bank’s vault for six days. During the standoff, a bond developed between captive and captor. One hostage, during a telephone call with Swedish Prime Minister, stated that she fully trusted her captors but feared that she would die in a police assault on the building. Source: Brittanica entry for “Stockholm syndrome”

About the author

Jessica Gaitán Johannesson grew up between Sweden, Colombia and Ecuador. Her fiction and poetry have appeared in publications in the UK, US and Ireland, including The Stinging Fly, Litro, Witness Magazine and The Scotsman. Her debut novel How We Are Translated was published by Scribe in the UK in February 2021 and the US in 2022. Since 2015 she works as a bookseller for the independent bookshop Mr B’s Emporium of Reading Delights in Bath, where she produces and hosts the Mr B’s Podcast. She’s active in the climate justice movement, facilitating workshops on the colonial roots of the climate crisis, and the connection between the climate crisis and migrant rights. Source: National Centre for Writing UK

See also our articles on

Sources

How we are translated”, Jessica Gaitán Johannesson, Scribe, 2022

“Translating the In-Betweenness of the Immigrant Experience”, Jaeyeon Yoo, Electric Lit, February 1, 2022

“How We Are Translated: Jessica Gaitán Johannesson”, London Review Bookshop, January 13, 2022

“How We Are Translated”, Meg Nola, Foreword Reviews, January/February 2022

“How We Are Translated by Jessica Gaitán Johannesson”, Alistair Mabbot, The Herald, January 18, 2022

“Livrädd and pissnödig. The anxieties and complexities of translation in How We Are Translated by Jessica Gaitán Johannesson”, Miranda France

Photo credit Cover photo of book @Amazon