“Rotwelsch”, the European travelers’ tongue, has united outcasts for centuries

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

Rotwelsch is an ancient language of the road, spoken by vagrants, refugees, merchants and thieves since the European Middle Ages. It means “beggar’s cant” and is based on a combination of German, Yiddish, Hebrew, Romani — the language of Sinti and Roma — Czech, and Latin. Rotwelsch is also known as kochemer loshn, an adaptation of the Hebrew khokhem, which means a wise person and loshn, tongue, or language. Martin Puchner, Wien professor of Drama and of English and comparative literature at Harvard University, tells us more about how he was initiated into Rotweisch in his recently published memoir, “The Language of Thieves”. During his early childhood, spent in Southern Germany, Puchner remembers seeing strange figures, dressed in long worn coats, who showed up at his family’s door, carrying bags over their shoulders. His mother would give them something to eat. When Puchner asked his father about these people and their language he replied that they were “people of the road, escaping to nowhere.” Their special language bound them together, because it distinguished those who belonged to the road from those who didn’t. Puchner’s father and uncle had had a lifelong fascination with Rotwelsch (the latter even wrote poems and translated the Bible, Shakespeare, and Goethe into the language).

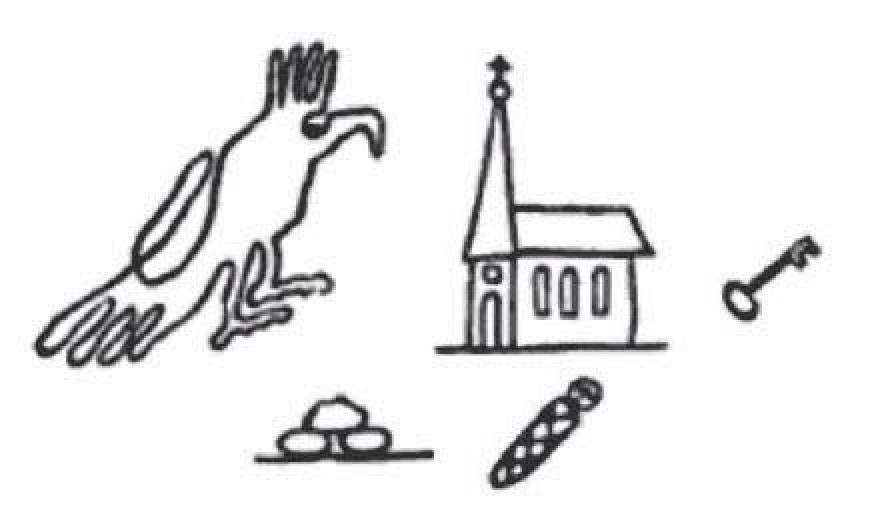

To help each other navigate a hostile landscape, Rotwelsch speakers also etched secret signs, or Zinken, that look almost like cuneiform or hieroglyphics. Zinken could warn travelers of an aggressive dog, mark a safe place to sleep, or invite collaborators to join a church robbery.

When Puchner later emigrated to the United States he was surprised to come across hobo signs, which he recognized as being derived from the Rotwelsch zinken. Central European vagrants had probably brought these signs with them in the 19th century, he says, a time of renewed immigration from German-speaking lands. But the peak of hobo zinken came during the Great Depression, when the signs were used in much the same way that Central European itinerants had used them: to navigate the difficult life on the road. The signs were adapted to suit the needs of their new users; American hoboes sometimes walked the road, but they also sneaked rides on trains, which is why a sign emerged, that of a rudimentary train engine, to mark a good place to hop on a train.

Throughout their 700 year history, scholars, religious authorities, and police, all tried to root out Rotwelsch. Martin Luther sneered at traveling beggars as “foreign, Jewish, and deceptive, the work of the devil”. In the 17th century, Puchner writes, the Thirty Years’ War and subsequent Peace of Westphalia created a world of nation-states and borders that criminalized vagrancy. But the postwar devastation itself also uprooted huge numbers of people, giving rise to a larger, more entrenched Rotwelsch culture. At one time or another, Puchner adds, Rotwelsch speakers have attracted the ire of every kind of oppressive ideologue in the modern world, including anti Semites, due to the Yiddish influence in their language.

According to Wikipedia some variants of Rotwelsch, often toned down, can still be heard among travelling craftspeople and funfair showpeople as well as among vagrants and beggars. Also, in some southwestern and western locales in Germany, where travelling peoples were settled, many Rotwelsch terms have entered the vocabulary of the vernacular, for instance in the municipalities of Schillingsfürst and Schopfloch. A few Rotwelsch words have entered the colloquial language.

In an essay for Zòcolo, a publication of the Arizona University, Puchner says that the existence and persistence of the language raises questions that connect with today’s American political struggles. How much mobility are we willing to tolerate from those who seek to cross borders? To what extent will we accept people who don’t talk like us? The author of a review for Harvard Magazine says the book is at its best when Puchner says that Rotwelsch is “a reminder that our settled lives are not always possible, that there are people who are unsettled.… Every order, if it is to avoid becoming oppressive, must accept disorder, every border must accept porousness, every state must accept statelessness.” Yes.

Sources

“Is a Secret Ancient Language of Wanderers a Harbinger of Our Future?”, Martin Puchner, Zòcolo, November 9, 2020

“Family History”, Marina N. Bolotnikova, Harvard Review”, November-December 2020

“The language of thieves”, Amazon