Félix Fénéon’s three-line “nouvelles”, an experiment in haiku journalism and insightful snapshot of life in the “Belle Epoque”

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

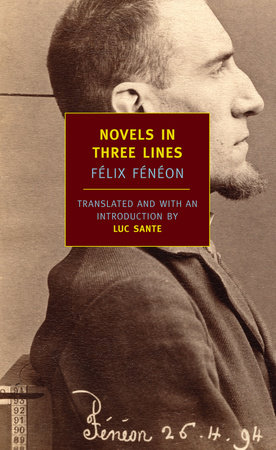

Félix Fénéon (1861-1944), was a writer, journalist, art critic, art dealer and publisher who “shook up the world of literature” in the early 1900s by inventing a new literary genre: the “news in three lines.” (1) Fénéon was employed by the the French daily Le Matin where in 1906 he wrote 1.220 short news items (known in French as fait-divers), “true stories of murder, mayhem, and everyday life, presented with a ruthless economy that provokes laughter even as it shocks”, as the New York Review of Books describes them. (2) His work has “the brevity and soul of a Maupassant and the journalistic realism of Zola, in the length of a Tweet”, says another reviewer (3). One thousand of these news reports were collected in the book Nouvelles en trois lignes, where nouvelles in French can mean both “news” and “novellas”. Luc Sante, a prolific writer and critic who translated the book into English, says the work demostrates, in miniature, “Fénéon’s epigrammatic flair, his exquisite timing, his pinpoint precision of language, his exceedingly dry humor, his calculated effrontery, his tenderness and cruelty, his contained outrage”.

Félix Fénéon, a precursor of the Oulipo movement

“Oulipans” have been considered by some as successors of Fénéon’s approach. The Oulipo group, founded in 1960 by writer and publisher Raymond Queneau, consists (mainly) of French-speaking writers and mathematicians seeking to create works using constrained writing techniques. (4) Famous Oulipians including Italo Calvino, Georges Perec and Harry Mathews. Georges Perec imposed upon himself an amazing linguistic and intellectual challenge when writing La Disparition, a 300 page novel without a single “E”, published in 1969. The novel is written in “lipogrammatic” style; a “lipogram” is a literary work in which one compels oneself strictly to exclude one or several letters of the alphabet, usually a common vowel, and frequently “E”. The first lipograms date back to the VI century BC and the word comes from the Greek leipográmmatos, “leaving out a letter”. The missing “E” is actually part of the plot of Perec’s novel, which follows a group of individuals looking for a missing companion, very cleverly called “Anton Vowl”. Perec later went on to write the novel Les Revenentes (1972), where “E” is the only vowel used. (5)

Fénéon’s work, an overlooked milestone in the history of Modernism?

Opinions are divided about the value of the Nouvelles and Fénéon’s legacy. In 1914, Apollinaire started a wider awareness of the Nouvelles by saying, in a newspaper column, that they had invented the “words at liberty adopted by the Futurists”. Luc Sante claims that the Nouvelles “depict the France of 1906 in its full breadth; that they have the perfection of haikai; that they are ‘Fénéon’s Human Comedy; that they have the same essence as the pointillists‘ adamantine dots; that they are like random photographs found in a trunk; that they parallel Braque and Picasso’s use of newspaper in Cubist collage; finally, that they represent a crucial if hitherto overlooked milestone in the history of Modernism”. (6) The New York Review of Books hails it as “a secret masterpiece, “a work of strange and singular art that brings back the long-ago year of 1906 with the haunting immediacy of a photograph”. (7) For others still it is an amusing concept, and enjoyable enough to dip into, but ultimately little more than a curiosity (8). Author Julian Barnes says the Nouvelles were “the journalistic equivalent of cocktail olives”, for which Fénéon “devised a new piquant stuffing”…(6)

The challenge of translating an “Oulipan” constrained literary work

George Perec’s La disparition has been translated into English and several other languages, including Japanese, Turkish and Catalan. All translators have imposed upon themselves the same or similar literary constraint, avoiding the most commonly used letter of the alphabet. The Spanish version contains no “A”s, which is the second most commonly used letter in the Spanish language (the first being “E”), while the Russian version contains no “O”s. See also our blog post on “Literary acrobatics: a 300 page novel without a single ‘E’ in it” @ https://bit.ly/350Uh4h and read more about Oulipo.

Author Julian Barnes says that English translator Luc Sante was “bravely undeterred” by critic Robert Herbert’s view that “Translating Fénéon would be tantamount to rendering a Sung landscape in department-store plastic” and considers that he has well conveyed the taut, sprung wryness of the original French. (6) It would be interesting to see what Sante himself says about his work (we have ordered the book, the introduction might provide some clues).

A taste of Fénéon’s three liners

An article in Broadstreetreview.com quotes some of Fénéon’s “three-liners”. Sometimes, says the author, the humor is straightforward: “If my candidate loses, I will kill myself,” M. Bellavoine, of Fresquienne, Seine-Inferieure, had declared. He killed himself. At other times he attains a weird surrealist humor: Again and again Mme. Couderc of Saint-Ouen, was prevented from hanging herself from her window bolt. Exasperated, she fled across the fields. There is sense of suspended time here. Was Mme. Couderc caught? Did she finally succeed at doing away with herself? Who knows? At least one piece is worthy of inclusion in the Greek anthology, the author adds, and Sante himself has commented on its epigrammatic quality: On the bowling lawn a stroke leveled M. Andre, 75, of Levallois. While his ball was still rolling he was no more. Fénéon also occasionally crafts “mini anti-government essays” in the guise of a news item: Through a clever game of alternating resignations, the mayor and town council of Brive have delayed the building of schools.

The Nouvelles en trois lignes on Twitter

The Nouvelles has its own Twitter account, called @novelsin3lines, which is no longer active-the last entry dates back to 2010-but, with 1000+ entries, appears to include most of the content of the book.

See more of our articles on “Linguistic curiosities” at this link

About cApStAn LQC

cApStAn Linguistic Quality Control is a high-profile language service provider with a holistic approach to multilingual projects: this ranges from translatability assessments, preparation of glossaries and translation guidelines-before translation commences-to delivering premium translations that are fit for purpose, and linguistic quality control post translation. The R&D department focuses on in-house development of web-based quality assurance applications and searchable translation memory management.

Read more about our translation and adaptation work @ capstan.be

Footnotes

- 1) In November 2019 the Paris Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris dedicated an evening event to Félix Fénéon, titled “Discovery Evening: F.F. and the Anarchists of Art”. It is the event’s organisers who refer to his work as shaking up the literary world and creating a new literary genre.

- 2) “Novels in Three Lines”, New York Review Books Classics, Amazon

- 3) Review of Novels in three lines, Library things, March 30, 2013

- 4) Oulipo stands for Ouvroir de littérature potentielle (Workshop for Potential Literature)

- 5) The Oulipo group also practiced what they called “anoulipism”, i.e. discovering constraints used by writers from other ages and cultures, wittily referred to as “plagiarism by anticipation”: they found constraints in the reversible poems of 3rd-century China, and acrostics in the Psalms and the narratives in Jorge Luis Borges’s 1941 The Garden of Forking Paths. These examples come from an interesting article in The Guardian which reviews the recently published (December 2019) Penguin Book of Oulipo, a selection of 100 Oulipian texts. The author of the article says lovers of puzzles and word games will relish some of the many sometimes deceptively simple constraints described in the anthology, such as the “snowball”, in which each successive line is one unit (a letter, syllable or word) longer, or the “prisoner’s constraint”, in which letters with ascenders or descenders (b, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, p, q, t and y) cannot be used. For Harry Mathews, author of the 35 Variations on a Theme from Shakespeare, “what distinguishes Oulipo from other language games, is that its methods have to be capable of producing valid literary results.” – “The Penguin Book of Oulipo review – writing, a user’s manual”, Tony White, The Guardian, December 18, 2019

- 6) Luc Sante is quoted in the book review titled “Behind the gas lamp”, London Review of Books, Julian Barnes, October 4, 2007

- 7) “Novels in Three Lines”, Book description and reviews, Penguin Random House, December 2019

- 8) “Novels in Three Lines” review, M.A.Orthofer, Complete Review blog “Literary Saloon“, April 10, 2009

- 9) “Give me three lines, and I’ll give you the world”, Andrew Mangravite, Broadstreet.com, December 14, 2008