ESRA 2025 Conference Update | The Evolving Landscape of Survey Methodology

By: Steve Dept, Founder – cApStAn

Despite an erratic Eurostar service on July 14th, arriving in Utrecht Central Station on a summer afternoon puts one’s mind to rest: the students know how to chill in troves, sipping drinks on terraces or on flat barges that ease along the water, cruising the streets on bicycles – not necessarily at a leisurely pace – and smiling. I was on time for the opening keynote and reception in the Stadsschouwburg (City Theatre) on the waterfront.

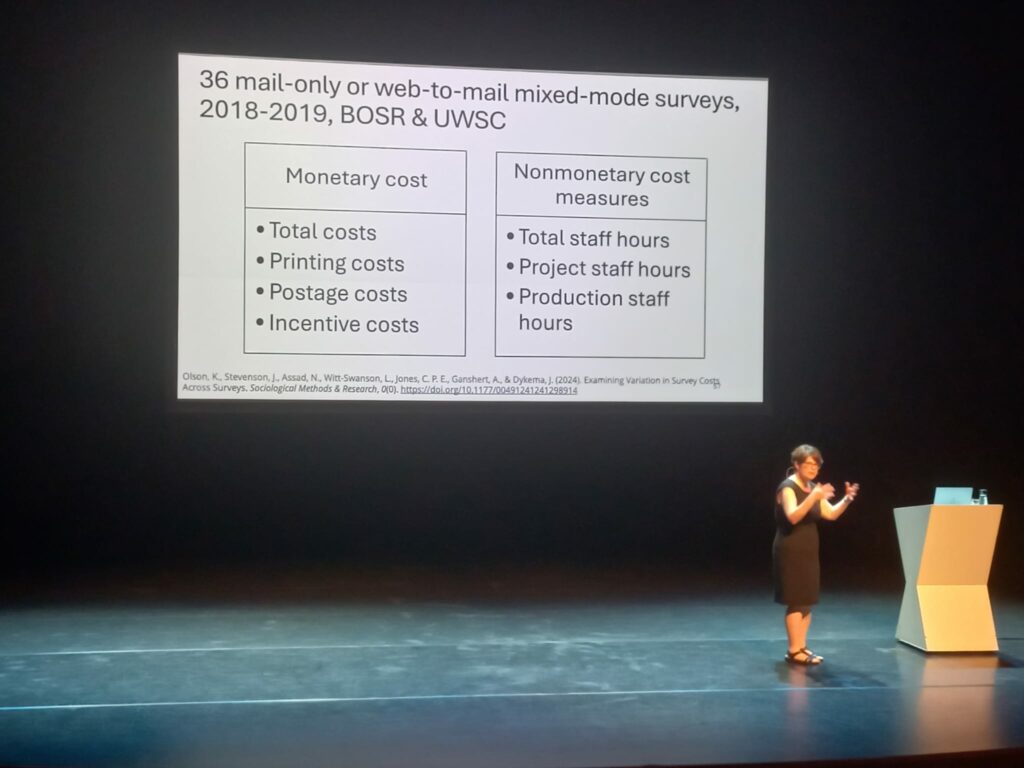

There where so many of the people we have worked with or intend to work with gathered there, some already basking in the late afternoon sun, others having a coffee. It was difficult not to talk politics at all with our American colleagues who had crossed the pond, or to leave the topic of AI alone, so the awkwardness was left aside and conversations were candid and lively. The opening keynote by Kristen Olsen, titled “From Mail Surveys to Chatbots: Changes in Survey Modes, Methods, and Data Sources Over Time” set the scene. When Prof. Olsen compares the costs of mail-only surveys with web-to-mail mixed-mode surveys, she doesn’t only look at monetary costs but also nonmonetary cost measures such as production staff and project staff hours. Saving printing or postage costs doesn’t adequately convey the whole picture.

In the Netherlands, restaurant kitchens may close relatively early, so everyone left the reception at 8:00 and we ate Indonesian food with like-minded peers. Consequently, everyone was up early and the morning sessions in the Ruppert building of the University Campus were packed.

I was delighted to spend the morning following the sessions around the European Values Study and the World Values Survey, organised by Vera Lomazzi, Kseniya Kizilova and Ruud Luijkx. The topics were rich, diverse and, of course, substantiated with a wealth of data: the evolution of gender roles across Western and Islamic countries; religious change in Europe; perceived essentials of democracy in mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan; an evaluation of measurement mode effects – you name it. When it comes to cross-cultural surveys, we all know that translation matters, but in this context, there is a special focus on culture-driven perception shifts. Time was well kept, and so there was always time for Q&A. It struck me that the questions, even when challenging, were asked in a helpful, constructive spirit. Researchers did not have to prove something, they wanted to understand everything.

The afternoon sessions covered a broad scope of survey research and methodology, too. I chose “Adapting survey mode in a changing landscape: Experiences from repeat cross-national, cross-sectional and general social surveys”, chaired by Daphne Ahrendt and Gijs van Houten from Eurofound, Tim Hanson and Nathan Reece from ESS HQ at the University of London. cApStAn has been involved in the translation or the translation verification of many the questionnaires used to collect the data, and we have contributed to resolving the language-related adaptations that need to be made when switching survey modes.

The Wednesday was at least as interesting, and I attended a session on web probing before the sessions on questionnaire translation began. Web probing is an activity we are involved in, too: we produce automated translations of responses to web probes (questions about survey questions) and use key words to automatically sort the responses in a number of buckets. At 11:00 a.m., the session “Questionnaire translation in a changing world: challenges and opportunities” began. A highlight for me, of course: eminent colleagues presented data from experiments that attempted to compare questionnaire translation by social scientists with translation by professional translators, with and without post-editing of machine translation. The surveys were actually fielded, so it was also possible to have an idea of how much translation matters (yes, the conclusion is clear in that respect: translation quality and data quality are closely interrelated).

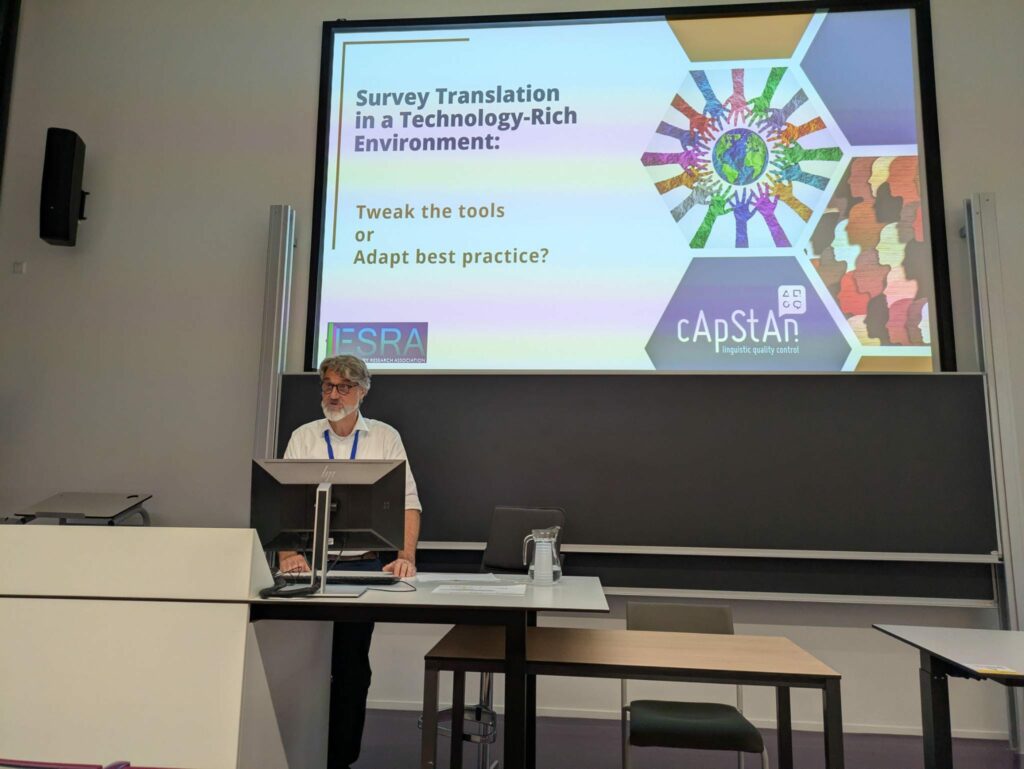

My own paper raised questions about survey translation guidelines, the gold standard, and the new tools that are available to perform this work. When keeping reliability and validity as our lodestar, should we closely adhere to existing best practices in survey questionnaire translation and customise the new tools so that they can accommodate these? Or have the new tools rendered some components of this best practice obsolete? New advances in machine learning, machine translation and large language models (LLMs) can bring efficiency gains but require an expertise that is not always available to survey methodologists. The presentation was well received, questions were asked (and continued to be asked over lunch).

I was delighted to end the day with the session “Survey research beyond the binary – Exploring the potentials, challenges and consequences of alternative measures for assigned sex, gender identity/expression and sexual orientation”, moderated by Verena Ortmanns, where I learnt a lot e.g. about continuous measures in gender expression and about guidelines to measure assigned sex, gender identity, sexual orientation and gender expression, for example.

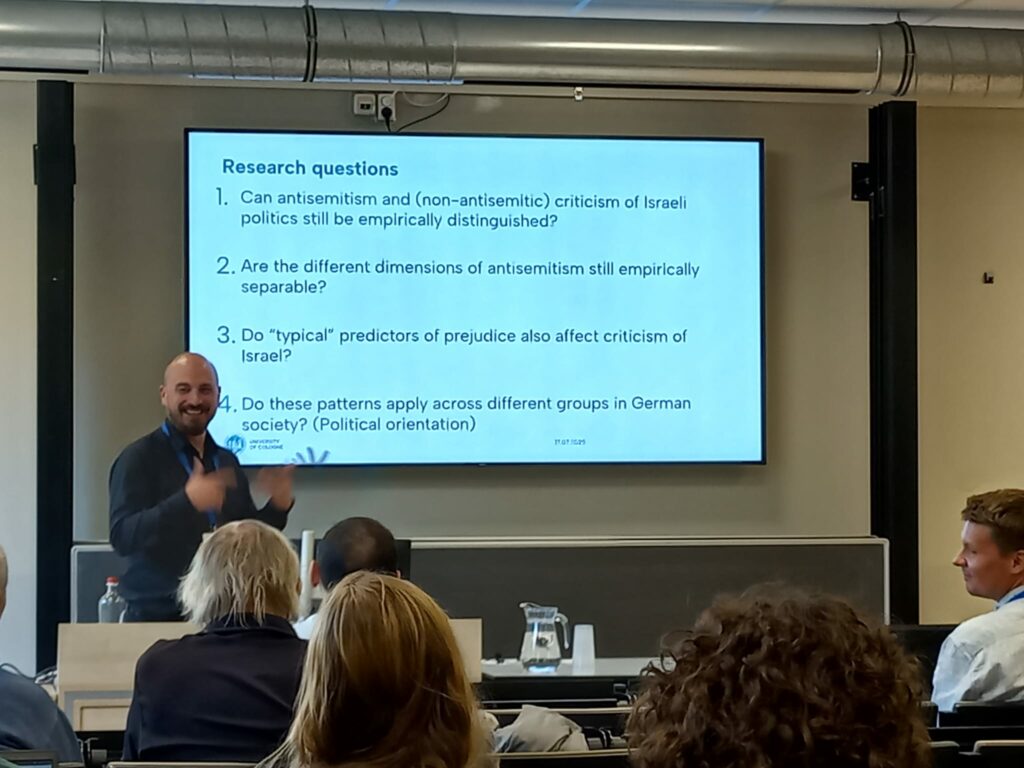

The Thursday morning, I attended the very insightful session “Sources, consequences and measurement of antisemitism”, moderated by Prof Eldad Davidov. where antisemitism was examined from different perspectives. This session was followed by a plenary session in memory of Don Dillman, under the them “We can do better”, introduced by Ver Lomazzi nad moderated by Daniel Seddig. Edith de Leeuw, Pablo Cabrera-Álvarez, Olga Maslovskaya, Carina Cornesse, Rory Fitzgerald and Bart Schouten each presented moving tributes to Don Dillman’s invaluable contributions to the field, often with a touch of humour.

Back on the train after lunch (I missed the Friday); I reflected on these three days packed with exchanges, meetings and thought-provoking conversations with researchers and field practitioners. I felt energised and inspired, and ready to resume our asymptotic relation to perfect survey translations: we keep coming closer to the ideal adaptation and never quite attain it. “We can do better” is certainly a positive message to take back to my colleagues.