Esperanto Day, July 26, celebrates the birth of a language aimed at fostering harmony among peoples. How is it faring today?

by Pisana Ferrari – cApStAn Ambassador to the Global Village

July 26, 2022, marked the 135th anniversary of the publication of the book “Unua Libro“, which introduced and described Esperanto, the language invented by Polish ophthalmologist Dr L. L. Zamenhof. In Esperanto, the word “Esperanto” means “one who hopes.” Having grown up in the multicultural but distrusting environment of Białystok, Zamenhof dedicated his life to constructing a language that he hoped could help foster harmony and peace between peoples. The goal wasn’t to replace anyone’s first language; rather, Esperanto would serve as a universal second language. Zamenhof believed that language barriers were a major reason for conflicts, and that an international language could serve as a bridge for communication and could foster harmony among peoples. “Were there but an international language, all translations would be made into it alone […] and all nations would be united in a common brotherhood”, he claimed. Zamenhof made Esperanto as easy to learn as possible, with no irregular verbs, and a simple, genderless, almost caseless grammar. Three-quarters of the root words are borrowed from Romance languages, the rest from Germanic and Slavic tongues and Greek. (1)

Esperanto may not have become as popular as Zamenhof hoped — or brought world peace — but, according to some estimates, there could be anything from around 100.000 to 2 million speakers. There are even an estimated 1.000 Esperanto native speakers, including some international figures such as Daniel Bovet, 1957 Nobel Prize Laureate in Physiology of Medicine. In less recent times notable Esperanto fans include authors Leo Tolstoi, J. R. Tolkien and Jules Verne. Esperantists are spread all over the globe, with particularly large pockets in Europe, as well as China (2), Japan (3), and Brazil. Esperanto has survived against some pretty steep odds: it could have faded away during both world wars, when its speakers were persecuted (4), or could have been killed off by the progressive rise of English, says Humphrey Tonkin, a distinguished scholar and an international authority on Esperanto. Instead, the development of Esperanto has continued unabated into the 21st century and Tonkin thinks idealism has a good part to play in it. A number of recent developments, including the advent of internet and of new technologies, have contributed to a renewed interest in the language.

How do you explain the appeal of Esperanto?

Esperanto has only ever been spoken by an assortment of fans and true believers spread across the globe, but to speak Esperanto is to become an automatic citizen in the most welcoming non-nation on Earth, reads an article in The Verge. Decades before internet Esperantists could have free accommodation with fellow Esperantists in 92 countries using the Pasporta Servo, or develop pen pals through Korespondantoj en Esperanta Lingvo (Plumaj Amikoj). It may be a small, widely dispersed, and self-selected diaspora, says the author of the article, Sam Dean, but wherever you go, there are Esperantists who are excited that you exist. This is the central appeal of Esperanto, he concludes. “There’s no money, no power, no marketing, no prestige — Esperanto speakers speak Esperanto because they believe in it, and because it’s fun to speak a foreign language almost instantly, after a couple months of rolling the words around in your mouth”.

How Esperanto is finding new life online

Many Esperanto speakers feared that internet would kill it. “With instant translation on Google,” says American Esperanto devotee John Drehner, in an article for the San Diego Reader: “you can stay in your silo and let the machines do the reaching out.” Gene Scott Keyes, professor of World Politics, peace activist and noted cartographer, says that, on the contrary, Internet has enabled Esperanto “to spread its wings further and faster”. Indeed. Esperanto boasts a Wikipedia (Vikipedio) site with over 300,000 articles (there are more Wikipedia entries written in Esperanto than articles in Danish, Greek or Welsh), and a Google search on the word “Esperanto” yields an impressive 160 million entries. In addition to giving more visibility to the language, internet has opened up interesting online e-learning opportunities, including the very popular Lernu (200+ k users). Language-learning apps like Duolingo (400+ k students) and Amikumu have helped to increase the amount of speakers of Esperanto, and to find others in their area to speak the language with. Internet has also provided a place for Esperantists to convene without having to travel to conventions or local club. There are over one hundred international conferences and meetings each year, the biggest is the International Esperanto Congress, which is held annually. The 107th edition of the congress runs from Aug. 6 to 13, 2022, in Montreal, Canada. It is organised by the Universal Esperanto Association (UEA), founded in 1908, the largest international organization for Esperanto speakers which has national associations in 70 countries and individual members in 120 countries (5,000+).

A lively art, literature, cinema and music scene

Esperanto culture includes art, literature, cinema and music. There are over 25,000 Esperanto books, both originals and translations. William Auld, the Scottish poet who wrote his greatest work in Esperanto, was nominated for the Nobel Prize multiple times (but never won). There are also several regularly distributed Esperanto magazines. Revuo Esperanto is the magazine used by the UEA to inform its members what is happening in the community; Monato is a general news magazine. Esperanto hosts the largest Braille publications in the world. There are currently radio broadcasts from China Radio International, Melbourne Ethnic Community Radio, Radio Habana Cuba, Radio Audizioni Italiane (Rai), Radio Polonia, Radio F.R.E.I. and Radio Vatican (Pope John Paul II gave several speeches using Esperanto during his career). In 1964, Jacques-Louis Mahé produced the first full-length feature film in Esperanto, titled Angoroj. Many more have followed since then. There are also a number of films, cartoons and documentaries that are not Esperanto originals but are subtitled in Esperanto and posted on YouTube. In 2013 a museum about Esperanto opened in China.

Why Esperanto is still relevant

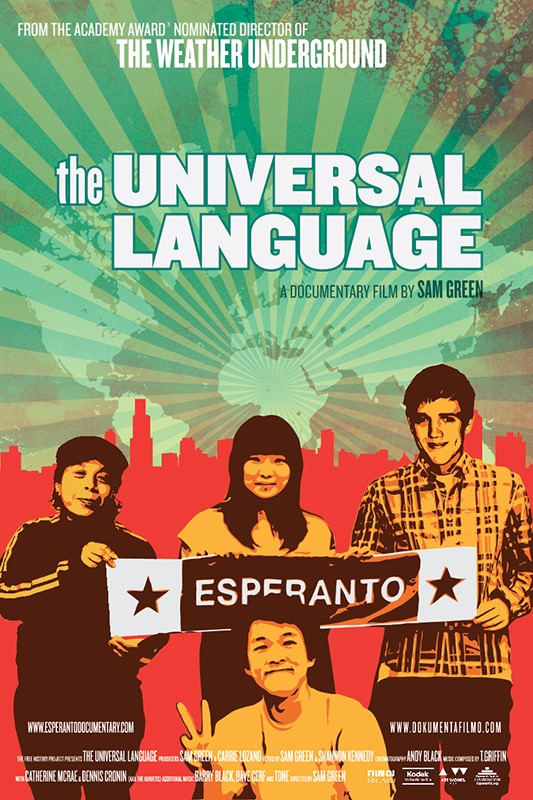

Wang Shanshan, and Zhong Xia, authors of an article for the CGTN, say that we live in a world that is increasingly fragmented, with man-made trade frictions, a resurgence of nationalism and a slow globalization trend, all the more fueled by the pandemic. Today, Esperanto couldn’t be more relevant to us, they claim. Whether this is the case or not, the increased visibility due to internet, the lively art, literature, cinema and music scene, the large numbers of young people signing up for e-learning and language apps, the opportunities for free travel and cultural exchanges, and the passionate activism of Esperanto youth organizations worldwide (including the organization of an annual International Youth Congress) bode well for its future. Academy Award nominated film director Sam Green, author of the documentary “The universal language”, says that, perhaps surprisingly, a vibrant Esperanto movement still exists today, and there at least three good reasons that justify investigating Esperanto or indeed learning it: idealism, practical advantages, and linguistic interest.

By Sam Green

READ MORE: Joshua Holzer, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Westminster College, USA, has just published a very detailed history of Esperanto, see: “A brief history of Esperanto, the 135-year-old language of peace hated by Hitler and Stalin alike“, The Conversation, July 25, 2022

Footnotes

1) Esperanto has been accused by some as being too “Eurocentric” as it does not not draw on a wide enough selection of the world’s languages.

2) Esperanto has a long and complicated history in China, leaving it an active present-day community. El Popola Ĉinio, the PRC’s first official Esperanto magazine, still publishes today online. China Radio International, formerly Radio Peking, is still broadcasting daily in Esperanto to listeners at home and abroad. China.org.cn, a news portal controlled by the State Council, has an Esperanto version. While these publications translate political propaganda as part of their work, they remain an important resource for Esperanto learners in China and elsewhere. Zaozhuang University in Shandong province established its Esperanto major in 2018 and, perhaps unbeknownst to most residents in the city’s resident, Asia’s first Esperanto museum, back in 2012. At its peak, the country had an estimated 300,000 to 400,000 speakers. The Chinese Esperanto League most recently reported 1144 members from China to the Universal Esperanto Association, but no one knows for sure how many Esperanto speakers there are in China today.

2) Esperanto has an almost unbroken history of organised activity in Japan dating back at least to 1906 and continuing today, supported over time by a diverse, bottom-up movement and embodied in a wide range of different ideas and practices. Esperanto has been read, written, spoken and sung by Japanese figures ranging from diplomats at the League of Nations to revolutionaries in prison, from leaders of religions old and new, scientists and doctors, to schoolchildren in rural villages. Source: “Rethinking the world through language: the role of Esperanto in modern Japanese history”, Ian Rapley, Cardiff University.

3) By the 1930s, both Germany and the USSR had outlawed Esperanto organisations. The Nazis exterminated speakers they came across in their occupied territories, while Stalin, who spoke of “the language of spies”, had Esperantists deported or shot (the Soviet government maintained controls until the late 1980s). In Japan in the 1930s, Esperanto speakers were similarly persecuted, and even killed. They were notably described at that time as being “like watermelons – green on the outside but red inside” (green was adopted early on as the colour of Esperanto). The suspicion that Esperanto was a communist plot made it similarly unpopular in Franco’s Spain, and many Esperantists had indeed fought on the Republican side during the civil war. And the persecution continues. Iran’s mullahs dislike Esperanto, and Saddam Hussein had one teacher of the language deported. In recent years, two Swedish Esperanto speakers were severely beaten by Tanzanian police for attempting to teach the language. Source: “A beginners guide to Esperanto”, David Newnham, The Guardian

Photo credit Shutterstock